Issue # 34 Ray Smith

Text by: Christian Viveros-Fauné

I BET YOU THINK THIS SHOW IS ABOUT YOU: RAY SMITH’S EL NARCISO DE JESÚS (THE NARCISSUS OF JESUS)

I’ve said if Ivanka weren’t my daughter, perhaps I’d be dating her.

—Donald Trump

The aliens have landed and they’re just like us, except more conceited. Predictably, they’ve brought with them a massive library of self-help books. Among those published during this current version of war of the worlds are Everyday Narcissism: Yours, Mine and Ours; Healing From A Narcissistic Relationship; How To Handle Narcissist, and, for those living under a rock for the last few years, Narcissism for Beginners.

Besides their putative subject matter, these books and one particularly self-reflective 2017-2018 art museum exhibition in Mexico all share one thing. For narcissism to be made great again in a culture that whines like a spoiled, Asperger´s addled toddler, these varied products demand that the world and its myriad self-advertisements take a good long look in the mirror.

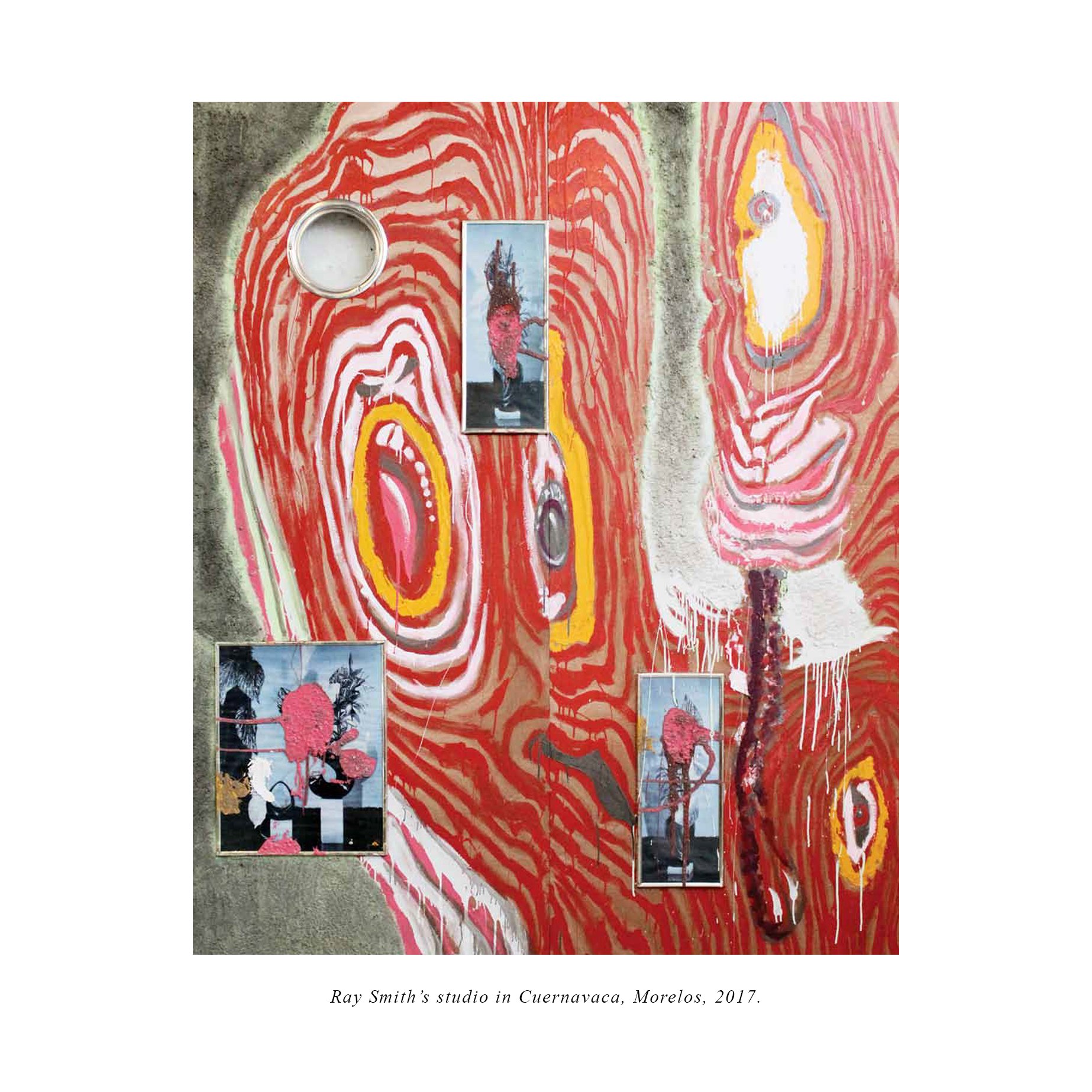

While the aforementioned abbreviated library of narcissism is available at an Amazon Fulfillment Center near you, the remarkable art display in question lives on in the catalog you currently hold in your hands. First staged at Cuernavaca’s storied La Tallera, the former studio and home of famed muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, the complex exhibition arrayed by Mexican-American artist Ray Smith—it consists of an all-enveloping display of drawings, paintings and sculptures—evokes a culture of narcissism overwhelming in both its pathology and appeal. To mention the patently obvious- the show includes more than one hundred and sixty-eight separate mirrors.

Titled El Narciso de Jesús (The Narcissus of Jesus)—after a florist’s sign the artist saw painted on the side of a delivery truck in Cuernavaca (“narciso” means daffodil in Spanish)—Smith’s exhibition focuses largely on the civilizationally malignant aspects of self-love, like those chronicled in less therapeutic, more analytical studies, such as Christopher Lasch’s 1979 jeremiad The Culture of Narcissicism, Jean M. Twenge and W. Keith Campbell’s 2009 diagnostic tome The Narcissism Epidemic and Kristin Dombek’s 2016 generational denunciation The Selfishness of Others. Among the conclusions inhabiting these books: We live in a culture so steeped in arrogance, self-absorption and navel-gazing we can no longer properly trust our own straight reflections.

Enter Smith’s carnivalesque hall of mirrors rendition of our rampant era of villainous egotism. A monumental collection of artworks that together aspire to the condition of both a contemporary art installation (as one might see in a world-class Kunsthalle like the newly refurbished La Tallera) and a 21st century political mural (such as the maestro Siqueiros produced on the Tallera´s premises from 1965 until his death in 1974), Smith’s collection of painted mirrors, transformed wooden doors and wood and expansion foam sculptures aspire to both channel and echo the age’s surfeit of messages and images. Their cumulative effect is, in a word, yuge.

Engineered as a particulate yet engulfing chaos that is at once riotous and individually “targeted,” Smith’s floor-to-ceiling reflective environment induces in the viewer both an odd feeling of self-satisfaction and self-annihilating vertigo. As a collection of individual pieces, the artist’s paintings and sculptures accrue like discrete works that repeat key motifs: crudely drawn figures, large Rorschach-like blots, manhole-style portals and obliquely painted sunrays. As a single artwork, the installation foments confusion. It does so, it should be said, deliberately by featuring distorted images painted on mirrored surfaces that cast a cockeyed view of the world back at their subject(s).

Besides proposing an installation that resembles a mini-Versailles on blotter acid, Smith’s calculatedly disorienting environment looks to imitate the internal conditions of clinical conceitedness. In doing so, the expansive artwork also provides a textbook experience of narcissism as defined by psychoanalysis: the malaise involves “an extreme self-centeredness arising from a failure to distinguish the self from external objects, either in very young babies or as a feature of mental disorder.” For the true narcissist, of course, Smith’s carny monsters and nightmarish splotches remain entirely beside the point. The kryptonite of the true egotist is inattention. Put in the lyrical terms of the American rock band Fall Out Boy: “I don’t care what you think, as long as it’s about me.”

But Smith’s comprehensive artwork also draws strength from two additional sources of high wattage conflict. The first is the ongoing psychic and human drama being played out like an episode of collective narcissism, nay a tantrum, at the U.S.-Mexico border—involving chiefly Donald Trump’s spectacularly demagogic promise to build a border wall between the countries and his subsequent scapegoating of immigrants of all types to the U.S. The second is the gigantic scale attendant to Siqueiros’ artistic legacy and the history of La Tallera. A studio that was intended to be, in the muralist’s own words, the first “real workshop for Mural Painting,” the site encourages wide-ranging monumental projects like Smith’s massive labyrinth of amour-propre.

La Tallera was conceived as an industrial-age factory for avant-garde art. “The workshop,” according to Siqueiros, was intended to be “huge, big, full of machines, with mobile scaffolds, with chemical laboratories, with plastic materials, with no need to suffer normal artistic privations, with a photographic department, with film cameras, with everything that a muralist would need, but also with the elements and accessories necessary to fully explore colors and the variability of geometrical forms in active space.”

Gendered as feminine due to the studio´s grooved tracks— the masculine “el taller” is conventionally used to refer to an artist’s atelier in Spanish—La Tallera was initially designed to produce XL-sized wall panels, a number of which remain on view in the world’s largest mural— The March of Humanity, housed at Mexico City´s Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros. Today La Tallera continues to embolden vision, a fact evident in Smith’s use of every aspect of the massive rectangular space. In the Mexican-American artist’s reconfiguring, his self-appointed mission with The Narciso de Jesús was not just to dream big, but to do so in ways that promoted a totalizing worldview.

Like Siqueiros, Smith proposed a type of artwork for La Tallera that scrambles both artistic and epistemological categories. Among these are the changing relations between the part and the whole in his large-scale artwork, the differences and similarities animating the juxtaposition of mural paintings with more conventional representations, and the active inversion of outside and inside within what Siqueiros considered to be a visual reality animated by multiple and simultaneous perspectives.

Like other modernists of his generation, Siqueiros was extremely well attuned and responsive to new technological and scientific developments. Among these were Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity and Sergei Eisenstein’s then novel use of the technique of montage. By synthesizing both of these advances with his own dialectical Marxism, Siqueiros arrived at a driving idea that he termed “polyangularity.” A break with static, single point perspective, Siqueiros’ painterly developments were intended to embrace not just revolutionary politics but the new science—most specifically the hyperbolic space baptized by the mathematician Hermann Minkowski as “the fourth dimension.”

Smith, for his part, has mobilized La Tallera in an attempt to further break with Euclidean space—in no small part to illustrate our newly exaggerated reality of informational rabbit holes, personal feedback loops, bias confirming Facebook newsfeeds and social media filter bubbles. If Siqueiros sought to explore and ultimately exploit the spatial possibilities of the fourth dimension, then the Brownsville-born Smith has sought to activate a known but as yet undefined set of coordinates that conjoins the digital and the physical representation of a fifth dimension.

Consider in this light Smith’s free-standing mirror paintings that—while reaching back into history to employ the same heavy-duty alkyd industrial paints used by Siqueiros in his murals—rips commentary from the headlines of the New York Times for cross-border reinterpretation in Spanish (one reads “Deep State,” a second “xenophobe”; a third, in a more emotive register, blasts: “Scream Goddamit”). These and other painterly elements reinforce the installation’s liminal or border-like state; a quality that is underscored by the inclusion of four “Border Paintings” Smith made in collaboration with the artist G. Tonatiuh Pellizzi: canvases which the artists covered with actual dirt and debris taken from real life paths trod by illegal immigrants.

A museum-wide installation designed as a total artwork, Smith´s paintings, sculptures and collaborations establish a portal or gateway of seemingly unrelated yet imaginatively affiliated phenomena à la internet. So it is, then, that Smith—a thoroughly bicultural artist who was literally born on the thin spit of no-man’s land that is ground-zero for today’s culture wars— enacts the dilemma of the split personality hundreds of millions of people presently experience experience as the divide between their virtual and their physical selves.

To mirror our current collective narcissistic “failure to distinguish the self from external objects,” Smith has fashioned a painted physical and reflective version of the internet that is also a panopticon and, in his own words, “a wormhole” that transports the viewer between two separate points in space-time in the manner of two popular but wildly dissimilarly characters. The first is Dr. who, the BBC sci-fi character who explores the planet in a time- traveling spaceship that takes the form of a British phone booth. The second is the 45th President of the United States: a true-life comic villain who hijacked a 28-year old invention to foil deliberative logic, the scientific method and civilized standards of behavior in an all-out assault on democratic values. In his hands and those like him, Ray Smith tells us, the internet is at once the fifth dimension—and a narcissist’s dream come true.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Ray Smith

Ray Smith (American, b.1959) is a painter and a sculptor. Born in Brownsville, TX, he grew up in Central Mexico. After studying fresco painting with traditional craftsmen in Mexico, Smith attended art academies in Mexico and the United States. Later, he settled in Mexico City. Often related to Surrealism in his unreal juxtapositions, Smith’s work is also characterized by a unique kind of magical realism. He creates illogical scenarios, that are full of surprises and special effects, by using dogs and animals as anthropomorphic beings. Smith considers an animal to be an “entity of the human figure.”

The artist has held more than 100 exhibitions around the world during the last four decades, mainly in the United States and Mexico, but also in Japan, Europe, and South America. In 1989, he participated in the Biennial Exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City. Smith exhibited at the First Triennial of Drawings at the Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona, Spain, and took part in the group exhibition called Latin American Artists of the 20th Century, which traveled from Seville, Spain, to the Musée National d’Art Moderne at the Pompidou Center in Paris, the Kunsthalle in Cologne, Germany, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Smith’s paintings are among the collections of many institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the Wurth Museum in Kunzelman, Germany, the Centro Cultural de Arte Contemporaneo in Mexico City, and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, amongst others. He currently splits his time between New York and Cuernavaca in Mexico.

Christian Viveros-Fauné (Santiago, Chile, 1965) has worked as a gallerist, art fair director, art critic, and curator since 1994. He was awarded the University of South Florida´s Kennedy Family Visiting Fellowship in 2018, a Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation Grant in 2009 and named Critic in Residence at the Bronx Museum in 2011. He co-founded The Brooklyn Rail in 1999, wrote art criticism for the Village Voice from 2008 to 2016, was the Art and Culture Critic for Artnet News from 2016 till 2018, and has additionally served as Chief Critic for Artland and Sotheby´s in Other Words. He has lectured widely at institutions such as Yale University, Pratt University and Holland´s Gerrit Rietveld Academie. He currently serves as Curator at- Large at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum and writes for The Art Newspaper and the Village Voice 2.0. He was recently appointed as Artistic Director for the 2023 Converge 45 Triennial (Portland, Oregon). He is also the autor of several books. His most recent, Social Forms: A short History of Political Art, was published by David Zwirner Books in 2018.