Issue # 31 Claudia Coca

Curated by Dorota Biczel

On Claudia Coca’s Landscapes of Desire and Oblivion, 2021

A rugged peak emerges from a dense cloud cover; swirling waves coalesce into the shape reminiscent of Latin America; the spinal cord in the center of a stretched leopard skin forms a distinct, mountain-range-like protrusion. In Claudia Coca’s Landscapes of Desire and Oblivion, earth, water, and an animal exist as equivalent entities. Depending on perspective and attention, they are as solid as they are amorphous. They congeal, come apart, and echo one another. The land, sea, and bodies of the Western hemisphere—that is, both that is considered non-human and that we tend to separate into “the animal” and “the human” today—undergird the artist’s ongoing body of work as persistent, recurring leitmotifs. The land, sea, and bodies were all subjugated as colonized territories following the European expansion of the fifteenth century. They had been appropriated and debased as commodities extracted by the Western colonialism. In many ways, Coca’s triptych aptly summarizes her larger project—the expansive, open-ended series Cuentos bárbaros. Through these “barbaric tales,” woven since 2015, the artist seeks to undo long engrained taxonomies and categorizations defining the elements of the “New World”: landscapes, minerals, and species.

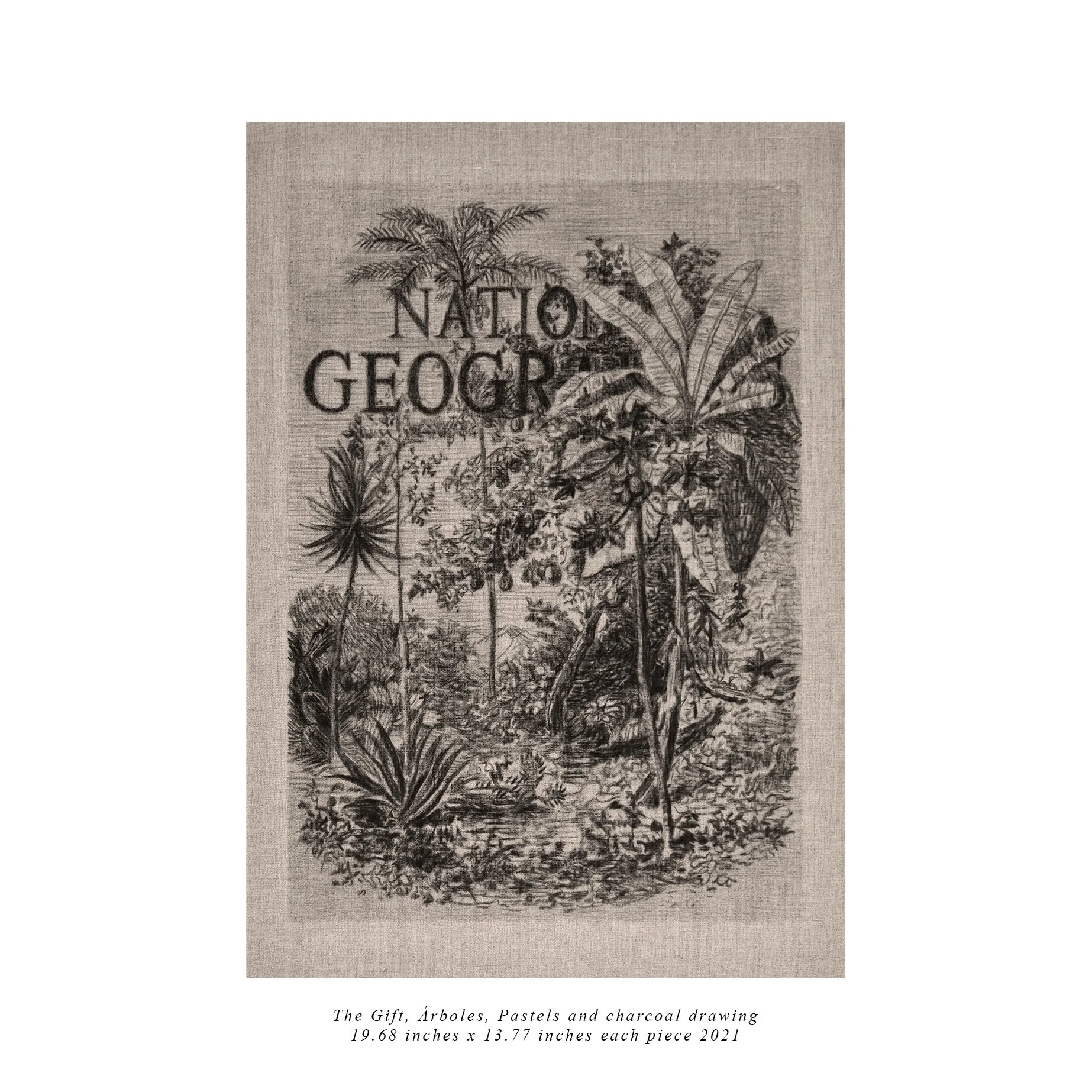

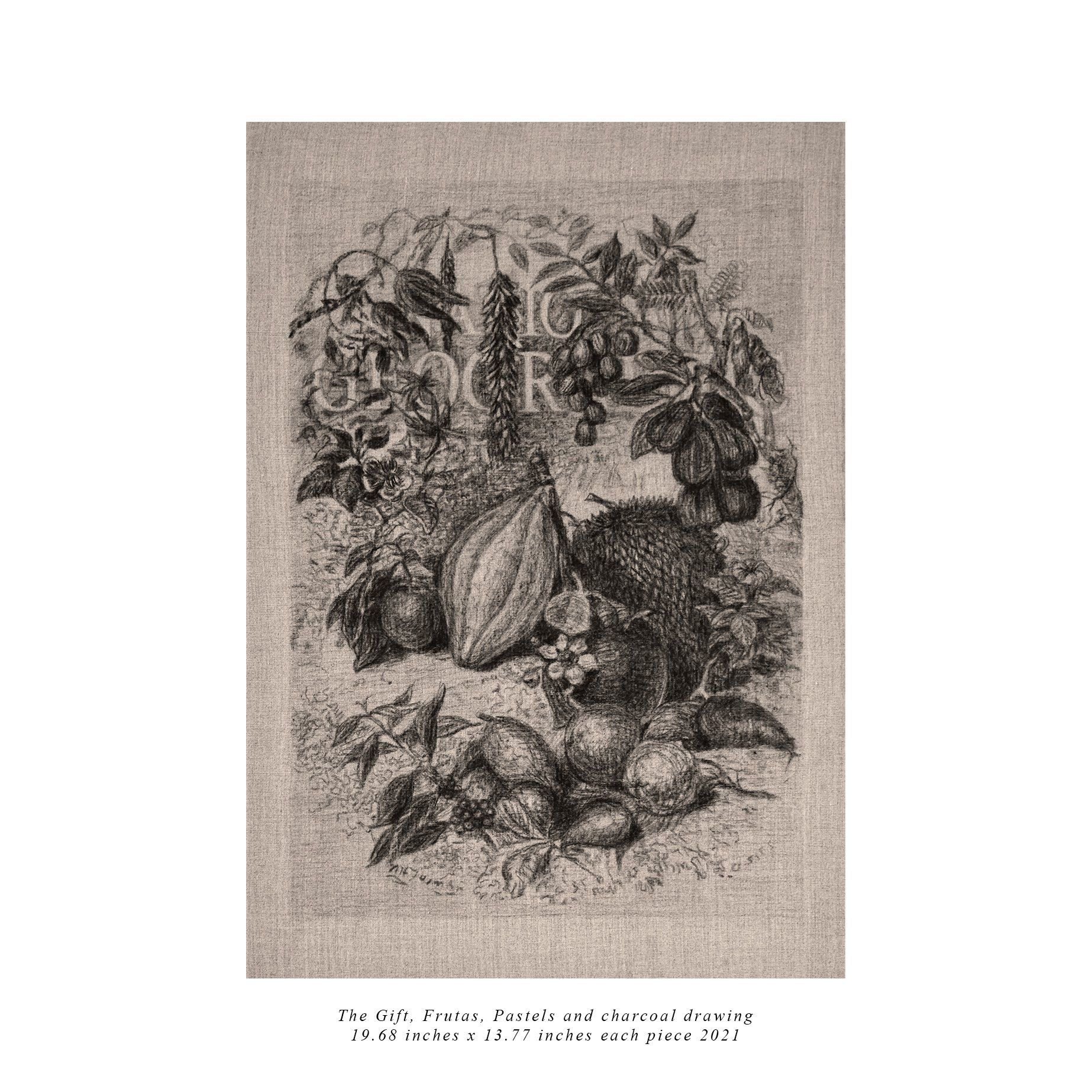

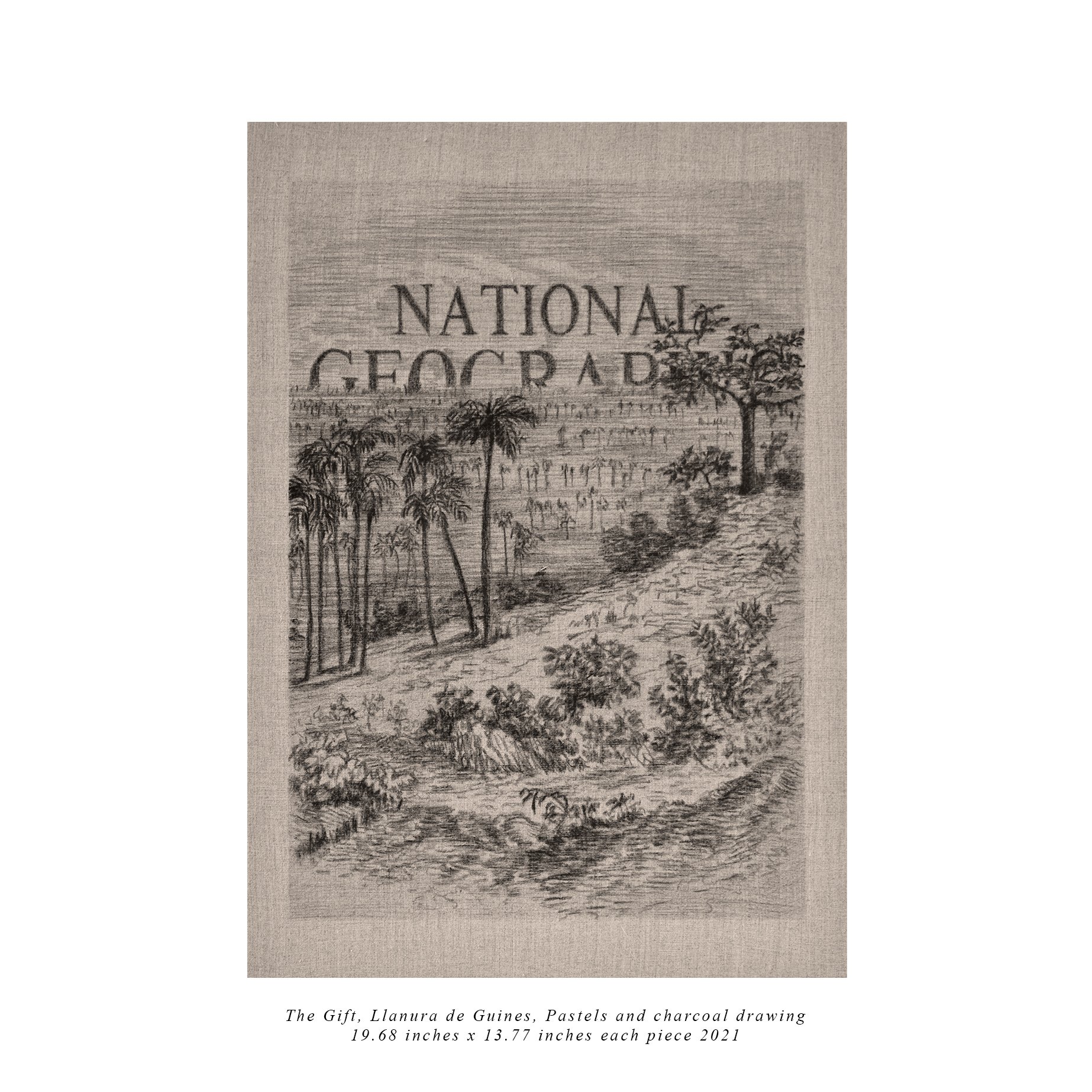

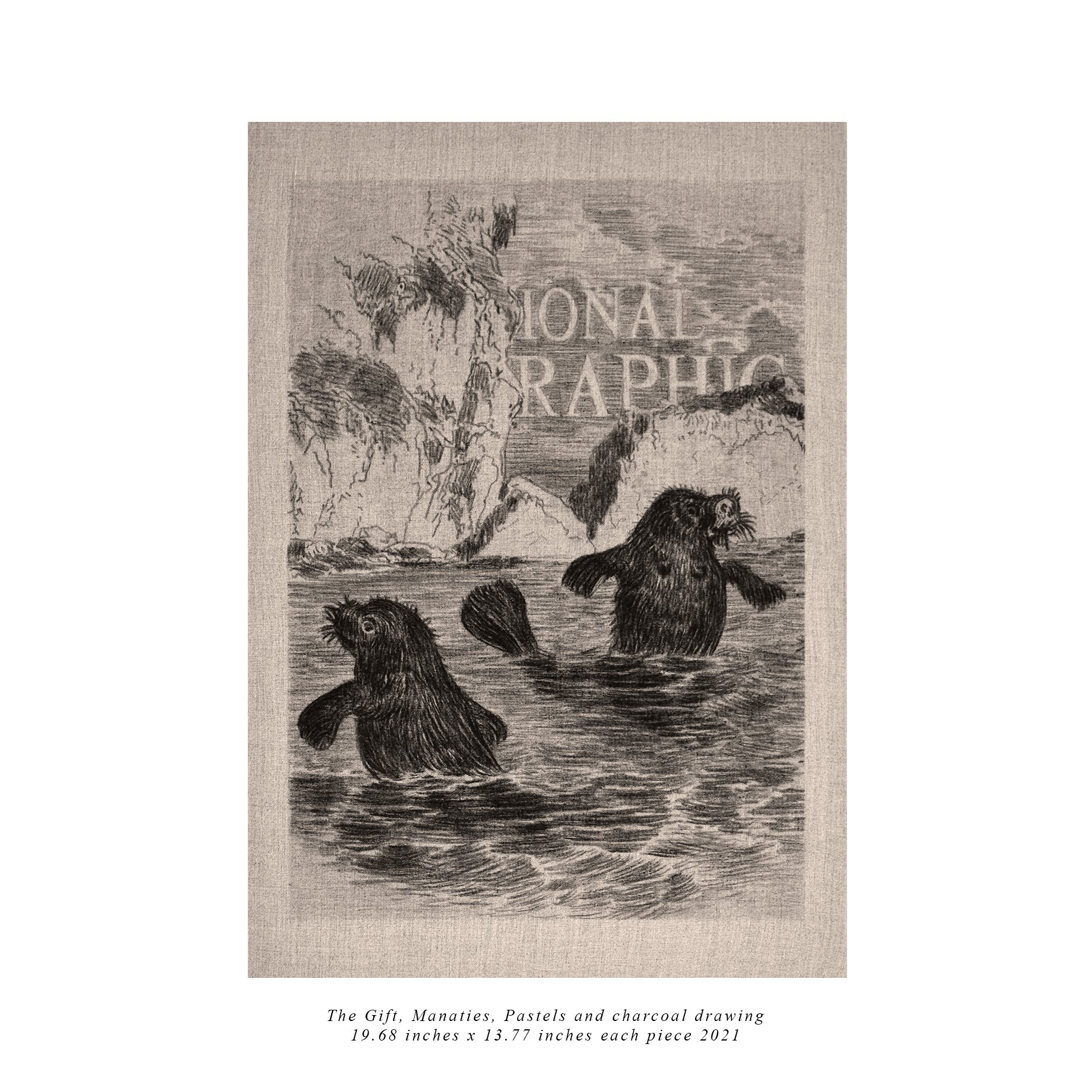

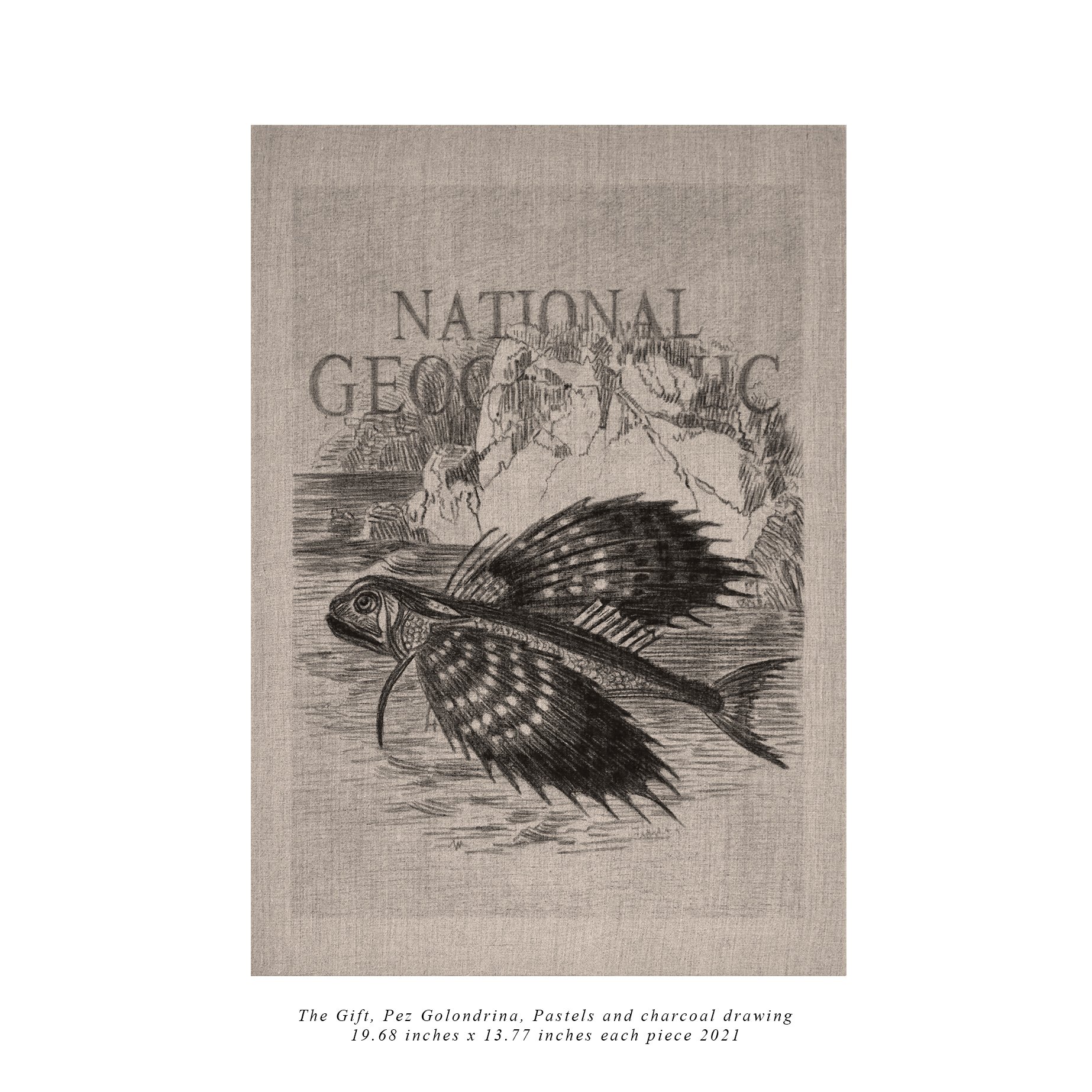

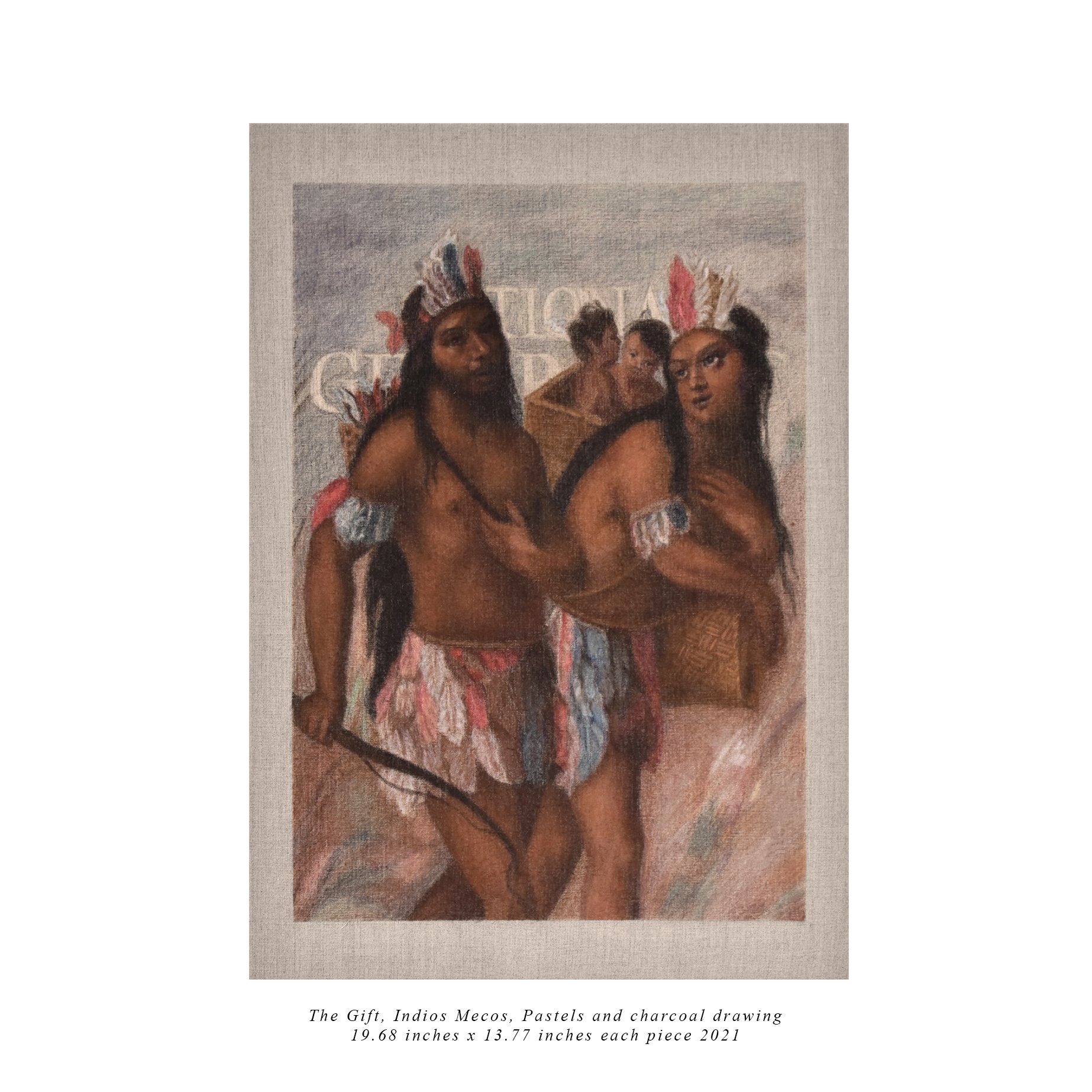

In Cuentos bárbaros, Lima-born Coca freely draws both from a thriving, lavishly illustrated popular science magazine, National Geographic, and the historical genre unique to the eighteenth-century Colonial Spanish Americas known as casta paintings. Her meticulous, near-photorealistic application of charcoal and pastel to coarse canvas collapses the distinction between contemporary images from the pages of a glossy publication and those appropriated from the varnished surfaces of centuries-old oil paintings. Through the artist’s methodical, analytical hatching, surfaces of juicy, fluid paint splinter and lush color photographs lose saturation. Coca thus muddies and blends chronologies and temporalities. In her work, the present and the past coexist in suspension. Representation and naturalism are rendered as conventions and, ultimately, as fictions.

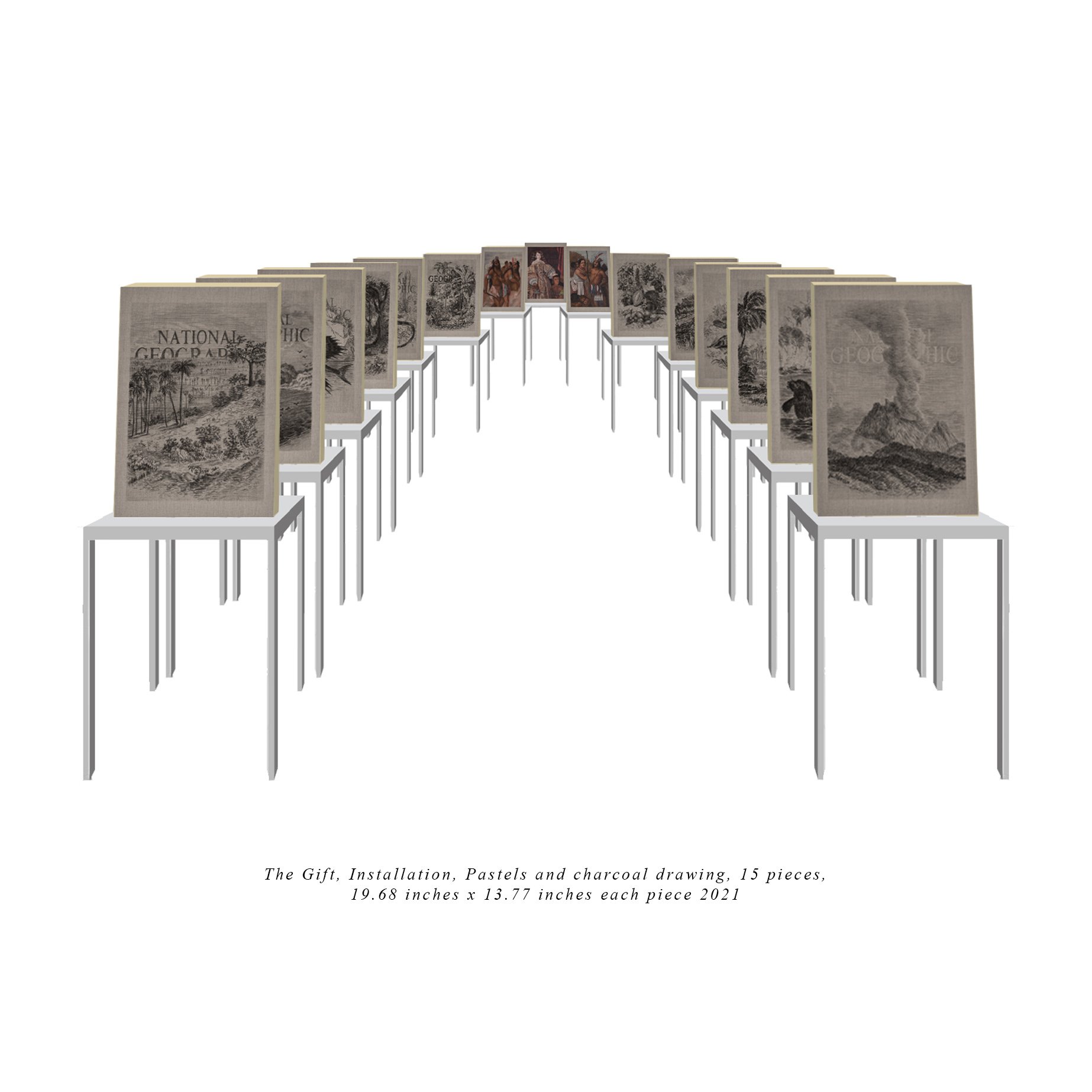

The Gift or New Spain’s Illustrations is an installation of fifteen canvases that mimic illustrated periodicals arranged on display. The monochromatic twelve seem to take the viewer on a journey deep into the “tropical” paradise, starting with distant views of a palm tree forest and a smoking volcanic peak, and focusing on micro views of “exotic” plants and creatures. However, defying a progressive, linear logic, instead of zeroing in on even more miniscule, imperceptible components of the world it pretends to introduce, the series culminates in three colorful images of people. In these pastel renderings, the iconic title of the magazine merges into the background of pictures produced long before the periodical was even established. Two distinct eighteenth-century representations of Amerindians—the good, “civilized” Indians from the series by Miguel Cabrera and the barbarian, meco Indians from the series by Andrés de Islas—flank the central portrait drawn from 1670 painting of María Luisa de Toledo y Carreto, the daughter of the Viceroy of New Spain, by Antonio Rodríguez Beltrán. In this Baroque court portrait, a lavishly clad pale young lady places her left hand on the head of a diminutive brown woman. Though the lady’s indigenous companion is also dressed in European garb, her face is entirely covered in tattoos, indicating that she had not always belonged in or to the court. The statement of the Museo del Prado, which currently houses the work, suggests “emotional attachment” between the two. However, the paternalistic gesture hints at domination and subjugation.

Both in The Gift and other subseries of her Barbarian Tales, Coca draws from the massive archive of the visual knowledge production that fueled the Spanish imperial project and laid the groundwork for the Enlightenment and contemporary science. She links up the images that borrow from the repertoire of covers of National Geographic to the collections of the National Museum of Anthropology in Madrid, which hold some of the most well known casta paintings, and traces a longer story of botanical and anthropological representation back to the Spanish Royal Cabinet of Natural History and beyond, to the maritime voyages of so-called discovery to the Americas. As historian Daniela Bleichmar has argued, vision was central to governing of the Spanish empire. Representations served as evidence of the unseen worlds beyond Europe and the European mastery over that rendered visible. Representations allowed to account for, classify, and stratify material possessions and populations. For five centuries, they produced and delivered the colonized and racialized.

Yet, in contrast to these centuries-old procedures, in Barbarian Tales, with every minute stroke of charcoal or pastel, Coca lovingly brings together all that taxonomies have torn apart. Under the veneer of reproduction and mimicry, her work is tactile and tangible: the lines created by the artist’s drawing tools mingle with and resist the weave of the canvas as if in an infinite exercise of magnetism. If the taxonomies’ colonizing purpose was to equate non-European bodies with animals and the land, and thus render them non-human, Coca celebrates the non-human as the only vital, generative, life-giving force that holds everything and everyone in balance. Ultimately, it is not the visible but the touchable that stimulates the desire and delivers the pleasure of being.

Dorota Biczel

Claudia Coca

Visual artist. Her work provokes a critical reflection on contemporary political and cultural issues like miscegenation, racism, gender and citizenship.

Among her individual exhibitions, the highlights are Landscapes of Desire and Oblivion (Ethan Cohen Gallery, New York 2021); All spaces are contemplated in my kingdom (Suero Project, Pamplona, Spain 2019); Don't say I don't know how to catch the wind (MUNTREF, Centro de Arte y Naturaleza, Buenos Aires, 2018); Barbarian Tales - Other Storms (Luis Miró Quesada Garland Room, Lima, 2017) and Barbarian Tales - Nearby Territories (Paseo Gallery, Lima, 2017); Mestiza, Anthology 2000-2014 (MAC, Lima); and, Revealed and Indelible (Museo de Arte de San Marcos, Lima, 2011). Mala Hierba / Yerba Mala was a bi-personal exhibition with the Paraguayan artist Claudia Casarino (Paseo Gallery, Lima, 2020)

Her work is part of various collections: Museo Reina Sofía (Spain); MALI Museo de Arte de Lima (Perú); Pérez Art Museum (Miami, USA); MUNTREF, Museos de la Universidad Tres de Febrero (Buenos Aires, Argentina); Museo del Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (Lima); MAC Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima (Perú); Museo de Arte de la Universidad Mayor de San Marcos (Lima, Perú); in addition to private collections in Peru and abroad.

She has been a founding member of the Civil Society Collective (Lima, 2020), the best known action is “Lava la Bandera” (Wash The Flag). Her work has been widely cited and published in texts on art and social studies.

She was invited to the production residency in MUNTREF: Centro de Arte y Naturaleza de Buenos Aires and to the 15vo Encuentro Global Sur (Argentina 2018). She has received the Luces Award 2014 for the Best Retrospective Exhibition, for her Anthological Solo Show Mestiza (MAC-Lima, 2014); the Second Prize of the National Painting Contest of the Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (2009); and a grant from the Third Colloquium on Human Rights in Sao Paulo, Brazil (2003); among other recognitions.

Dorota Biczel is a Polish-born art historian, curator, and writer. She has published and curated internationally on the subjects that intersect art, material experimentation, social movements, and spatial and gender politics. Her current book manuscript is tentatively titled Precarious Subjects: Non-object Art, Migrations, and Political Transitions in Peru, 1968–1990. Biczel holds a PhD in art history from the University of Texas at Austin and an MFA in graphic arts from the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts. At present, she serves as an executive director and curator of Houston Center for Photography.